Rural Post-Acute Care: Healthcare Leaders Offer Practical Solutions to Workforce Challenges

Dr. John Schnelle is Hamilton Chair of Geriatrics and Director of the Center for Quality Aging at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) in Nashville, Tennessee. He and his team have been working to improve transitions of patients from their tertiary facility to skilled nursing facilities (SNF) for post-acute care (PAC).

While his team’s creation of standardized data collection has had success, the biggest barrier they encountered was communication breakdown with partnering SNFs. “Everyone can agree with the need for a uniformed communication process for transitions of care,” said Schnelle. “The problem was that there is such a high turnover rate that makes it very difficult to get people competent in using those pathways.”

Across the country, turnover rates for nursing care centers reached 43.9% for all employees and over 50% for registered nurses, according to the latest American Health Care Association Staffing Report. Recruitment and retention challenges are common across rural healthcare entities providing PAC. Empowering and training staff, maximizing community partnerships, involving community health workers, and applying new technology are just some ways for rural healthcare leaders to create incentives for staff to join, or stay on, a healthcare team.

PAC Transitional Care Model Creates a Win-Win-Win

Dr. Mark Lindsay is a pulmonologist at Mayo Clinic Health System in Wisconsin. In the year 2000, he initiated a proposal to improve transitions from Mayo’s tertiary hospitals (Eau Claire and Rochester) to their outlying Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs). Lindsay stated, “Provider handoffs and transitions between facilities are two of the areas we score the lowest in healthcare.”

Lindsay referred back to a Transitional Care model he helped develop for a skilled nursing facility in Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, for patients on ventilators. The rate of patients weaned from ventilators with this program was over 60%, and nurse assistant turnover rates dropped to half of the SNF’s normal rate, falling much lower than industry benchmarks.

Lindsay thought that the team-based concept used in that model could work just as well for non-ventilator patients in a rural PAC hospital setting. “Rural hospitals have a positive environment for a patient and their families,” he said. “[Staff are] very committed and passionate about rural healthcare and they are really good at what they do. So there are big opportunities.”

He applied the concepts of enhancing the team experience, expanding on each clinician’s abilities, and using existing staff and resources to PAC teams in rural settings. The model proved to be a “win-win-win”: a win for the tertiary hospital, a win for the receiving CAH, and, most importantly, a win for the patient.

“We know that staff burnout in healthcare is through the roof. By promoting a positive culture and creating a positive work environment that is team-based, we can overcome some of the obstacles to recruiting and retaining staff in rural communities,” said Lindsay.

So far, this model has been implemented in 11 out of 12 Mayo Clinic Health Systems’ CAHs. Patient satisfaction rates and willingness to recommend a Mayo facility reached 92%. Referrals from Mayo Clinic to CAH Transitional Care improved by 500%. Through a joint venture, Lindsay continues to train healthcare systems around the country in post-acute care solutions. Outside of Mayo, an additional 44 CAHs have adopted the Transitional Care model.

A transitional care team visits with a patient at Deer Lodge Medical Center in Montana. This Critical Access Hospital is one of 44 outside of Mayo Clinic Health Systems that adopted the Transitional Care model.

Empowering Staff Takes a Culture Shift

Lindsay teaches that creating a positive work environment starts with empowering staff – especially nurses, therapists, and nurse assistants. “Teamwork, comradery, the culture – all those things can really make a difference in recruiting and retaining,” said Lindsay. He recommends every member of the multidisciplinary team be included in bedside rounds, giving those working the closest with the PAC patient a say in their care plan and leveling the hierarchical playing field. Lindsay came up with the acronym “CREATE” as a tangible and simple way for teams to implement the CAH Transitional Care model’s key characteristics:

Lindsay explained, “These principles are vital day in and day out to bring out the best in all team members and to create an environment where people can continue to grow, expand their skill sets to be the best they can be, and most importantly, expand the capabilities of the team.” Take cheerfulness. Lindsay said that the top two reasons why a patient recommends a hospital is how well the care team works together and the cheerfulness of staff. Taking the time to recognize jobs done well is a simple but powerful way to influence staff attitudes.

When Lindsay started the Transitional Care model at Mayo Clinic Health System in Bloomer and Osseo, Wisconsin, the PAC patient census was around four, the average patient census of most CAHs today. Because of the CAH Transitional Care model, Bloomer and Osseo’s PAC services frequently exceed 14 patients and swing bed days have tripled. Patient and employee satisfaction rates have been consistently high and the model has been a point of attraction for recruiting nurses and therapy staff. At first, the hospital used the staff they had to run the program. After the patient census increased, they hired more staff and now offer 24/7 respiratory therapy.

“We are seeing that the model works independent of geography,” said Lindsay. “This program can expand the capabilities for a rural hospital to care for these patients locally and to do it as well or better than anyone else.”

Because Lindsay’s Transitional Care model uses current staff and available resources, this model can work well for CAHs that already have a high nurse-to-patient ratio. By spreading the work among other members of the transitional care team in line of their scope of practice, it can help ease the burden on physicians. “It really moves a lot of that work from the physician to the team members and leverages the team. We know as we deal with physician shortages, this kind of team-based care is going to become more and more vital.”

Utilizing Community Health Workers to Strengthen Communication

In his white paper, New Models for Rural Post-Acute Care, Lindsay references studies that show poor communication in a healthcare setting contributes to medication errors, increased costs, patient harm, and even deaths. Vanderbilt’s Schnelle said that one solution for communication breakdown in post-acute care settings is continuous education of new staff: “It’s not just a matter of training someone once and then you are done. The training needs to be ongoing – incorporated in day-to-day activities.” He recommends “hospital huddles” as an effective practice. “Rather than taking them into rooms and doing a training with a blackboard, training happens right on the floor. You don’t need to spend 40 minutes, but only five to 10,” said Schnelle.

At Lexington Regional Health Center (LRHC) in Nebraska, hospital huddles are a daily occurrence. Each morning, transitional care teams meet to discuss their patients’ progress and goals. Among the clinicians and support staff on the team are community health workers (CHWs). Hiring CHWs who both understand and can communicate with Lexington’s growing multicultural population (now 10% Somali and 67% Hispanic) was one of CEO Leslie Marsh’s top priorities when she first joined in 2010. “My question was: How can we take care of patients and be more inclusive?” she recalled. “It was a matter of ‘we need to be delivering value and we need to be taking care of our community.'”

Since a beef packing plant opened in Lexington nearly 30 years ago, cultural differences and language barriers continued to create communication challenges between staff and patients. Now, CHWs who also serve as interpreters rotate within transitional care teams to ease the communication between staff and PAC patients recovering after an acute hospital stay. Marsh referenced Maria Reyes, a Latina CHW who specializes in behavioral health and has gained the trust of her population. “She’s really made a difference in the way that we understand what is happening with our patients,” said Marsh.

Community Health Worker Maria Reyes (right) and Interpreter Sahra Ali (left) work to ease communication between patients and clinicians at Lexington Regional Health Center.

Reyes not only makes regular visits to the patients while they are in the hospital’s swing bed program following an acute stay, but also meets with the patient before a planned surgery or clinic visit. She brings concerns back to the LRHC’s transitional care team in order to set the patient up for a successful discharge or transition of care. If the patient is discharged to the local nursing home or home health agency, Reyes travels on her own time to ensure the patient understood all the instructions that were relayed before the transition. These extra efforts to smooth communication makes the transitional care team’s work with each PAC patient more effective.

Embracing Community Partnerships and Developing New Nurses

VNA Home Health Hospice, a service of Eastern Maine Health System, is continually looking for ways to maximize the skills of every clinician and keep registered nurses working at the top of their license. To do so, staff explore partnerships that can come alongside home health clinicians. Leigh Ann Howard, RN, MSN, CHFN, is the director of VNA’s home health program and specialty programs. She helped establish their Faith Community Nursing Program to engage parish volunteers in providing basic in-home care for their fellow congregants following an acute hospital stay.

Volunteers can have a medical or non-medical background, but all are vetted and trained to provide social, psychological, spiritual, and physical care. The volunteers help meet some of the patient’s needs, allowing VNA clinicians to provide a higher level of medical care within their scope of practice, maximizing their time and skill set.

Some partnerships are informal in nature but just as beneficial, like the lobstermen who ferry home health clinicians to the islands off the coast of Maine so they can make a home visit. Other partnerships are still being explored, such as engaging paramedics in delivering PAC in patients’ homes through community paramedicine. “So many things are interconnected in many different ways,” said Howard. “It takes being very nimble, meeting the need that’s there, and continuing to offer a variety of different programs.”

Like many rural healthcare services, Maine’s aging population and outmigration of youth are top challenges of recruitment and retention efforts. Currently, the number of nursing graduates in Maine aren’t enough to fill the vacant nursing positions across the state.

Dr. Alana Knudson, Project Area Director and Co-Director of the Walsh Center for Rural Health Analysis at NORC, led a study finding that recruitment of therapists and nurses who were comfortable going into people’s homes to provide home healthcare services was a challenge for some agencies.

“Providing care in the home setting is very different than in the acute setting, particularly when most home health providers go to a patient’s home alone. Most new graduates have been trained to work in acute care settings with a team of other staff and do not have the skills and experience to treat a patient in their home,” said Knudson. “We need to develop curricula that include the home setting as part of healthcare education and training so that we have an adequately trained workforce to meet the growing demand for post-acute care in the home setting.”

In Maine, VNA’s Vice President of Nursing and Patient Care Services Elizabeth Rolfe has created change on the state level to include strategic onboarding and in-house training for new nurses to succeed in home healthcare. She recalled her initial idea: “If everyone is out there trying to recruit experienced nurses…if we have to compete with all the hospitals, care management roles, primary care physician practices, then maybe our solution is to take the opposite strategy and, say, develop workforce of the future and bring these folks in earlier.”

Until 2015, state law required nursing graduates to gain one year of nursing experience before they could work in home healthcare. Moved by the state’s growing nurse shortage and over 30% increase in VNA’s clients, Rolfe took action. She worked with the Home Care & Hospice Alliance of Maine to draft changes to the law. The change allowed new nurse graduates to start home healthcare immediately after graduating and required the hiring facilities to include onboarding initiatives to ensure a successful start for new nurses.

After the legislation passed, VNA put measures in place: Responsibilities are added slowly and under supervision while new nurses can take advantage of a mentoring program and support groups. Their new externship program for nursing students is gaining popularity, and VNA has gone from being short-staffed to having more applications than positions available.

Telemonitoring Cuts Down on Windshield Time

Although home health episodes billed to Medicare have increased by over 60% since 2001, home health in rural and frontier locations has become more of a challenge. Knudson links this challenge to reimbursement limitations: “Delivering home healthcare is cost-prohibitive in many rural and frontier communities because of windshield time. You do not get reimbursed from Medicare for the time it takes a healthcare provider to travel to and from a patient’s home. Covering staff’s travel time to outlying areas without insurance reimbursement may be very expensive for rural home health agencies.”

The growing use of telehealth has provided another solution to help far-reaching patients needing post-acute care services. VNA started a telehealth home monitoring program to help monitor patients and cut down on some of the PAC home health visits. Upon receiving a referral, patients are stratified by risk and distance to qualify for one of VNA’s 400 remote monitoring systems. For instance, patients living on one of Maine’s islands would have higher priority than one who lives in urban south Maine.

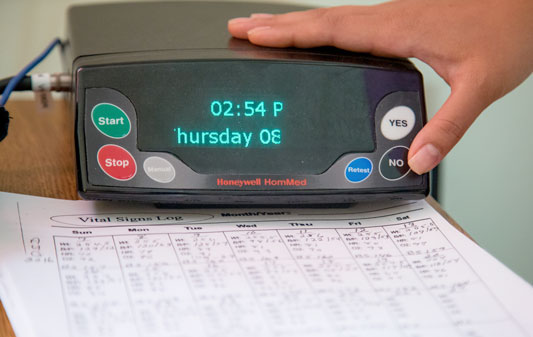

Transportable machines are installed in a patient’s home to help monitor vital signs. Every morning, the machine reads their vital signs and transmits the information to a team of specially trained nurses and therapy staff. Knudson sees telehealth as an answer not only for overburdened staff, but also for better patient monitoring: “It may improve outcomes because it keeps the patient engaged with their healthcare providers on a consistent basis. Once a change is noted, the home health providers can determine if a phone call to the patient or a home health visit is appropriate, and the health issue can be addressed in a timely manner.”

Telemonitors help VNA clinicians detect irregular patterns in patients’ vital signs from a distance.

Telehealth has also been approved as a method of conducting CMS’s face-to-face requirements between provider and patient, a move that will help reduce time, cost, and delays. It’s the use of alternative methods that help VNA deliver services to their growing number of patients. While they continue to grow relationships in rural regions not yet familiar with telemonitoring, they have become a model program. In 2017, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) conducted a site visit to evaluate VNA’s telehealth home monitoring program. Information gathered from this visit informed the research and recommendations presented in the 2018 MedPAC Report to Congress: Medicare Payment Policy.

“You’ve got to embrace them,” Rolfe said of innovative workforce solutions. “We are a poor, rural state with an aging population and workforce challenges. So you’ve got to leverage anything you can to serve these rural communities.”

The article was originally published on the Rural Health Information Hub:

https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/rural-monitor/post-acute-care-workforce/